Mathematics Careers Word Search Answer Key

It was pretty much a typical Friday at Ogilvy Toronto. The whole creative department was crazy busy, when another big project dropped out of the sky. Scanning the stressed-out teams overdue for a decent weekend break, this was not the best news ever. At least this assignment was a gem, and I quickly decided the best art director for the job was Luke*–my go-to miracle worker.

"Luuuuke . . . hey, just how busy are you?"

"Busy."

"Too busy to create a logo for a new coffee? The client's giving us the whole brand identity assignment; they just pulled the job from Tap–totally blew it. But now the calendar's brutal. The VP wants to see thinking in a week. I know, it's really tight."

Pause. Eyes shut tight. Then: big smile. "Like I'm going to say no to my next gold Pencil. I don't think so."

I knew he'd do a great job, as always. He lived for work like this. With so little time for a process that would normally take at least twice as long, I resolved to give him space and wait until the day before the command performance to see his solutions.

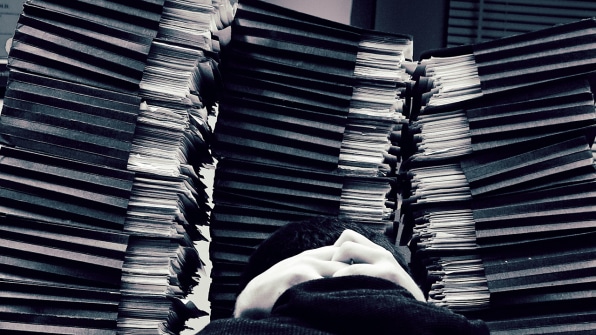

Anyone looking on as Luke took me through his designs late the following Thursday would have noticed the color draining from my face as each logo was worse than the one before it. Nine, 10, 11. Nope, there's no 12. The best of them wouldn't get a nod from my 9th grade art teacher. I knew my talented employee wasn't suddenly a hack. The explanation was now horrifyingly obvious: He never really had the time to squeeze in this job. The meeting would have to be cancelled. Merde.

Why didn't Luke just say no, explaining he was stretched too thin? It was a classic case of yes-icide, that self-sabotaging reflex to please rather than say the much harder word: no.

We all do it. Almost everyone with a pulse is conflict-averse. We don't want to let people down, deal with unhappy faces, look weak, risk being branded a slacker. We fear the judgment, the loss of popularity, repercussions real and imagined. From the nervous grad new to the workforce to the experienced and highly successful, we tell ourselves we'll get it done, we'll be heroes; it'll all work out in the end.

I've said yes when I should have said no many times myself, sometimes with plenty at stake. I gave a green light to a hire for a top position on one of our biggest accounts when the senior client threatened to pull the business if we didn't get the opening filled quickly. I wasn't convinced the accomplished person we had in front of us was the right fit; I wanted more time to be sure the casting was right. But in a stare-down with a hyperventilating managing director, I caved. They got their leader. A very bad one, as it turned out. Hindsight being 20-20 and all, I don't think taking more time would've cost us the account; but the wrong hire had an impact arguably worse than the loss of that business would have had.

The yes that's a short-term fix and averts displeasure often sabotages the longer-term goals. When you consider the much greater penalty of wearing a bad result, it's really worth a rethink in that moment of decision. The boss that's kicking cans for an hour when she doesn't get her way is nothing compared to the moment of hearing you've blown the client relationship. Or worse.

Yes-icide—that tragic, mediocrity-fuelling choice—is preventable. The next time you're under pressure to do the wrong thing (which usually happens when it's urgent), take a deep breath and the time you need to think through yes or no. Ask yourself:

- Is my yes aligned with achieving the long-term goal?

- Is yes aligned with the brand's values? My company's? With mine?

- Does the data support a yes?

No to any of the above likely means no is the right answer. Which doesn't make saying it any less daunting. You can probably find the conviction you need by looking at which choice carries the greater penalty. Ask yourself:

- What's the worst that can happen if I say yes?

- What's the worst that can happen if I say no?

How you deliver an unwelcome no is the difference between being the messenger they want to shoot and a person who's appreciated for saving everyone from a bad decision. Painting a vivid picture of the consequences of saying yes can help open people's eyes to the other side of the question. Make them feel the full weight of yes. (It's a step most of us don't think to take in the heat of the moment, but my art director could have stopped me cold with vivid description of C-minus designs limping into the client's boardroom.) Then be part of the solution. If you have a different approach to the problem, share it. If you don't, pitch in to figure it out.

The brave soul who says the hardest word may pay a price in the short term. My partner Janet Kestin and I have both been thrown off accounts, and early in her career, she was once fired over too many no's. But when you become known for having the guts to speak your mind, put a stake in the ground for the sake of everyone's success and find better ways to navigate the rough waters, you'll land as a person people respect, a leader. Oh, one more bit of advice: The next time your employee tells you no for all the right reasons, thank them for it.

*A composite character.

Janet Kestin and Nancy Vonk are the cofounders of Swim, a creative leadership training lab that works with people in advertising, marketing, technology, and beyond to create fearless leaders. They were previously the co-chief creative officers of Ogilvy Toronto, the agency behind Dove "Evolution" and other famous work for Shreddies, Maxwell House, and others. Their career-long involvement in mentoring, teaching, and training resulted in Pick Me, an advice book for advertising professionals based on their popular blog, Ask Jancy. They are currently writing a business book on women, life, and work for Harper Collins.

[Yarn Strings: Madlen via Shutterstock, Workload: RollingFishays via Shutterstock | Flickr users Horia Varlan, Angelo Amboldi]

Mathematics Careers Word Search Answer Key

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/1683359/the-hardest-word-why-saying-no-is-key-to-your-long-term-success

Posted by: perkinsbrerefrommen.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Mathematics Careers Word Search Answer Key"

Post a Comment